It would be nice if Palestinian Muslims in Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria, and Gaza would approach their holy month of Ramadan (which begins this weekend) as intended by their religion – as a month of fasting, charity, prayer, contrition, and reflection.

Many devout Muslims do so, but it is also true that Ramadan frequently has been celebrated with Muslim, especially Palestinian, violence. Ramadan is exploited as an excuse for ramped-up holy war against Israel.

Those with long memories will remember that Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against Israel on Yom Kippur 1973 – during the month of Ramadan. In many Arab circles, it is still called the “Ramadan War.” Somehow the prayer, contrition, and reflection did not inhibit that sneak attack that slaughtered 2,700 Israelis.

Neither did the fasting. Egyptian and Syrian soldiers were given an exemption from fasting because they were engaged in the religious duty of killing infidels.

Those with short-term memories, which excludes many individuals in the Biden White House and Blinken State Department, can easily ascertain that Israel’s enemies have long used Ramadan to murder Jews. In 2016, Hamas gleefully labeled the murderous attack on the Sarona Market in Tel Aviv the “Ramadan Operation” and celebrated the “First Attack of Ramadan.” Other terrorist attacks on Jews soon followed, making that year’s Ramadan a particularly bloody month in Israel.

It is not even limited to Jews. In 2016 and 2017, ISIS twice bombed a popular street in Baghdad during Ramadan, killing hundreds of Muslims. During that same 2016 Ramadan, a radical Muslim attacked the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, murdering 49 people. These are not isolated examples. Arabs have historically fought vicious wars against each other during Ramadan.

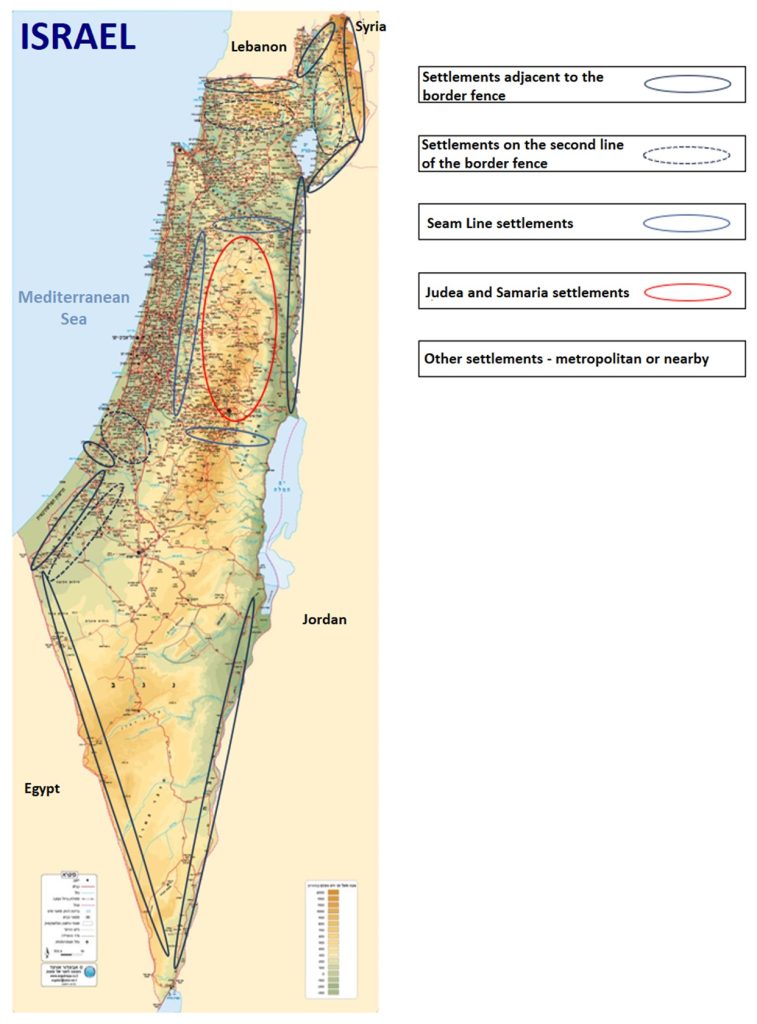

And sure enough, again this year, everybody fears “escalation” during Ramadan, especially since Hamas and its mouthpiece the Al Jazeera broadcasting network are religiously calling for expansion of the “Al Aqsa Flood” (i.e., the current war launched by Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack) to Jerusalem and the West Bank via terrorism and uprising.

And so, the defense establishment in this country is warning Israeli leaders to pay deference to Ramadan, to be extra cautious during Ramadan, and to do nothing to “provoke” Muslims on Ramadan – especially in and around Jerusalem’s Temple Mount – because Muslim emotions are oh-so-very sensitive during that month.

President Biden even has gone as far as to hint that Israel should halt its war against Hamas in Gaza to allow Muslims to piously observe Ramadan and, supposedly, tap into some of that famous Ramadan charitable spirit, leading Hamas to reverently melt toward a magnanimous hostage deal. (Halevai, I wish it were to be so.)

To a Jew and an Israeli, such sentiments sound bizarre, because they are bizarre. As the sage Rabbi Steven Pruzansky (formerly of Teaneck NJ and now of Modi’in) brilliantly has written, “I do not recall ever becoming so agitated over the Ten Days of Repentance between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur that I felt the urge to run out and attack innocent gentiles, or even guilty ones. Nor have I ever heard of that passion afflicting any Jew.”

“For that matter, it is inconceivable to any Jew – or any normal, moral, right-thinking person – to yell “God is Great” as a prelude to murdering, raping, marauding, beheading, exploding, stabbing, shooting innocent people, for whatever reason. Perhaps good Muslims should use this Ramadan for soul searching and how best to uproot this savage evil from their midst.”

It is the soft bigotry of low expectations that so-called security experts, politicians, diplomats, and statesmen nod their heads and say, “Well, of course, tensions always run high during Ramadan, and as such Jews should keep a low profile, because Muslim violence must be anticipated during the holy month.” Such a sentiment insults the majority of the world’s Muslims, as well as our intelligence. It is the very definition of surrendering to bullies rather than confronting them and vanquishing them.

This leads me to Palestinian-Jordanian impudence and Israeli infirmity in and around the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Look at how the government of Israel was tied-into-fits this week with urgent consultations on how and whether to impose anti-riot limits on Arab visitors to the two Muslim shrines on the Temple Mount during the upcoming Ramadan month.

This comes against the background of the threats described above, and stepped-up Jordanian and the Palestinian Authority efforts in the international arena to warn of the “dangers of any attempt to unilaterally alter the status quo at the holy site,” and “to reaffirm Jordan’s role as custodian of the Islamic and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem.”

They describe Israeli visits to the Temple Mount and the quiet, unofficial Jewish prayer quorums that sometimes gather there as “stormings” and “violent incursions” into Al-Aqsa, and as the “Judaization” of Jerusalem and its Muslim holy sites.

The inversion of truth contained in the above presentation is utterly galling! If anybody has unilaterally, brazenly, and violently changed the status quo on the Temple Mount over the past 25 years, it is radical Palestinian and Islamic actors who have turned it into a base of hostile operations against Israel, instead of protecting it as a zone of prayer and peace.

Israel, on the other hand, has acted with utmost restraint in the face of Arab assaults.

The Wakf and Islamic movement provocateurs have attacked Jewish visitors to the Mount, Jewish worshipers at the Western Wall below the Mount, and Jewish worshippers on their way to the Western Wall. They have attacked Emiratis and Bahrainis praying in Al-Aqsa mosque (because these countries signed Abraham Accord peace treaties). They have greatly restricted visitation rights to the holy mount for all non-Muslims and hijacked the pulpits in the mosque on the mount to preach hatred and violence against Israel.

The Wakf also has conducted vast, illegal construction projects on the mount and beneath it, willfully destroying centuries of Jewish archaeological treasures. (Four hundred trucks full of archaeologically rich rubble were unceremoniously dumped by the Wakf into the Kidron Valley. Thousands of artifacts from the temple periods have been since found in this rubble.)

Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas continues to stoke a broad-scale campaign against the authenticity of Israel’s historic rights in Jerusalem. In September 2015 he screeched about “filthy” Jewish feet that were “desecrating” holy Islamic and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem. “Al-Aqsa is ours and so is the Church of the Holy Sepulcher,” he bellowed. “They [the Jews] have no right to desecrate them with their filthy feet. We won’t allow them to do so, and we will do whatever we can to defend Jerusalem.”

At the same time, the PA-controlled Wakf has allowed ISIS, Hamas, Islamic Movement, and Turkish flags to fly on the Temple Mount in violation of all understandings, as well as blood-curdling banners with calls to annihilate Israel and the Jewish people.

This inflamed and despicable discourse now is being picked up by gullible (and not-so-gullible) Western progressives, who blabber about Israel’s “unprovoked” and “unacceptable” actions on the Temple Mount, “excessive” force, and “violations” of the “status quo.”

Even well-meaning Western spokespeople, like the State Department spokesman, have fallen victim to the Big Lie, with mollycoddling mumbo-jumbo about the need for “all sides to de-escalate and respect the sanctity and status quo of holy sites in Jerusalem.”

All sides should de-escalate? Status quo? Sanctity of holy sites? What the heck are they talking about? There is only one side, the Arab side, that purposefully has escalated the violence in Jerusalem and defiantly defiled Har HaBayit over the past 25 years! It is the Palestinians who have turned Al Aqsa and the entire mountain plaza into extra-territorial headquarters for the propagation of blood-curdling Big Lies about Israel.

In fact, Palestinian violence and Islamic exclusivism have become the new Temple Mount status quo. This is the status quo Western leaders demand that Israel preserve?

Alas, the governments of Israel seem to have gone mute in the face of the slanders at the heart of the Palestinian-Islamic narrative regarding the Temple Mount and the Jewish presence in Zion. Even now, when Hamas and its allies in Judea and Samaria are at war with Israel, Israeli leaders continually prefer to keep things quiet and “restore calm” after every wave of Palestinian assault and to swear fealty to a “status quo” that is long dead.

To top it all off, Jordan has the nerve amidst all this to ask Israel for additional water allocations. Even as Jordanian Queen Rania continues to deny and downplay the October 7 attacks, and Prime Minister Bisher Al-Khasawneh and Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi lambaste Israel with the most vicious anti-Israel rhetoric, Jordan wants an additional 50 million cubic meters of water over and beyond amounts Israel is obligated to provide under the 1994 peace treaty. This is chutzpah par excellence.

But hey, in the pious spirit of Ramadan, what’s 50 million cm. of water among friends?

Published in The Jerusalem Post, March 9, 2024; and in Israel Hayom. March 10, 2024.